Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Statement to the press conference (with Q&A)

Autor: Bancherul.ro

Autor: Bancherul.ro

2014-02-07 11:09

Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A)

Mario Draghi, President of the ECB,

Frankfurt am Main, 6 February 2014

Ladies and gentlemen, the Vice-President and I are very pleased to welcome you to our press conference. We will now report on the outcome of today’s meeting of the Governing Council.

Based on our regular economic and monetary analyses, we decided to keep the key ECB interest rates unchanged. Incoming information confirms that the moderate recovery of the euro area economy is proceeding in line with our previous assessment. At the same time, underlying price pressures in the euro area remain weak and monetary and credit dynamics are subdued. Inflation expectations for the euro area over the medium to long term continue to be firmly anchored in line with our aim of maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2%. As stated previously, we are now experiencing a prolonged period of low inflation, which will be followed by a gradual upward movement towards inflation rates below, but close to, 2% later on. Regarding the medium-term outlook for prices and growth, further information and analysis will become available in early March. Recent evidence fully confirms our decision to maintain an accommodative stance of monetary policy for as long as necessary, which will assist the gradual economic recovery in the euro area. We firmly reiterate our forward guidance. We continue to expect the key ECB interest rates to remain at present or lower levels for an extended period of time. This expectation is based on an overall subdued outlook for inflation extending into the medium term, given the broad-based weakness of the economy and subdued monetary dynamics. With regard to recent money market volatility and its potential impact on our monetary policy stance, we are monitoring developments closely and are ready to consider all available instruments. Overall, we remain firmly determined to maintain the high degree of monetary accommodation and to take further decisive action if required.

Let me now explain our assessment in greater detail, starting with the economic analysis. Following two quarters of positive real GDP growth, developments in recent data and surveys overall suggest that the moderate recovery continued in the last quarter of 2013. Looking ahead, our previous assessment of economic growth has been confirmed. Output in the euro area is expected to recover at a slow pace. In particular, some improvement in domestic demand should materialise, supported by the accommodative monetary policy stance, improving financing conditions and the progress made in fiscal consolidation and structural reforms. In addition, real incomes are supported by lower energy price inflation. Economic activity is also expected to benefit from a gradual strengthening of demand for euro area exports. At the same time, although unemployment in the euro area is stabilising, it remains high, and the necessary balance sheet adjustments in the public and the private sector will continue to weigh on the pace of the economic recovery.

The risks surrounding the economic outlook for the euro area continue to be on the downside. Developments in global money and financial market conditions and related uncertainties, notably in emerging market economies, may have the potential to negatively affect economic conditions. Other downside risks include weaker than expected domestic demand and export growth and slow or insufficient implementation of structural reforms in euro area countries.

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, euro area annual HICP inflation was 0.7% in January 2014, after 0.8% in December. This decline was mainly due to energy price developments. At the same time, the inflation rate in January 2014 was lower than generally expected . On the basis of current information and prevailing futures prices for energy, annual HICP inflation rates are expected to remain at around current levels in the coming months. Over the medium term, underlying price pressures in the euro area are expected to remain subdued. Inflation expectations for the euro area over the medium to long term continue to be firmly anchored in line with our aim of maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2%.

Both upside and downside risks to the outlook for price developments remain limited, and they continue to be broadly balanced over the medium term.

Turning to the monetary analysis, data for December 2013 confirm the assessment of subdued underlying growth in broad money (M3) and credit. Annual growth in M3 moderated to 1.0% in December, from 1.5% in November. Deposit outflows in December mirrored the strong sales of government and private sector securities by euro area MFIs, which, in part, could be related to adjustments by banks in anticipation of the ECB’s comprehensive assessment of banks’ balance sheets. These developments also affected annual growth in M1, which moderated to 5.8% in December but remained strong. As in previous months, the main factor supporting annual M3 growth was an increase in the MFI net external asset position, which continued to reflect the increased interest of international investors in euro area assets. The annual rate of change of loans to the private sector continued to contract. The annual growth rate of loans to households (adjusted for loan sales and securitisation) stood at 0.3% in December, broadly unchanged since the beginning of 2013. The annual rate of change of loans to non-financial corporations (adjusted for loan sales and securitisation) was -2.9% in December, after -3.1% in November. The January 2014 bank lending survey provides indications of some further stabilisation in credit conditions for firms and households and a smaller net decline in loan demand by enterprises. Overall, weak loan dynamics for non-financial corporations continue to reflect their lagged relationship with the business cycle, credit risk and the ongoing adjustment of financial and non-financial sector balance sheets.

Since the summer of 2012 substantial progress has been made in improving the funding situation of banks. In order to ensure an adequate transmission of monetary policy to the financing conditions in euro area countries, it is essential that the fragmentation of euro area credit markets declines further and that the resilience of banks is strengthened where needed. This is the objective of the ECB’s comprehensive assessment, while the timely implementation of additional steps to establish a banking union will further help to restore confidence in the financial system.

To sum up, the economic analysis confirms our expectation of a prolonged period of low inflation, to be followed by a gradual upward movement towards inflation rates below, but close to, 2% later on. A cross-check with the signals from the monetary analysis confirms the picture of subdued underlying price pressures in the euro area over the medium term.

As regards fiscal policies, euro area countries should not unravel past consolidation efforts and should put high government debt on a downward trajectory over the medium term. Fiscal strategies should be in line with the Stability and Growth Pact and should ensure a growth-friendly composition of consolidation which combines improving the quality and efficiency of public services with minimising distortionary effects of taxation. When accompanied by the decisive implementation of structural reforms, these strategies will further support the still fragile economic recovery. Governments must therefore continue with product and labour market reforms. These reforms will help to enhance the euro area’s growth potential and reduce the high unemployment rates in many countries.

We are now at your disposal for questions.

* * *

Question: I have noted the position you have taken, that you are continuing to monitor emerging market volatility. I think we’d be interested to know what, in your assessment, is the cause of the current phase of emerging markets’ foreign exchange volatility. What measures do you see that might be appropriate for the ECB to bring to bear in order to deal with any threat to euro area export markets as a result of an ongoing round of such foreign exchange volatility? Thank you.

Draghi: The discussion today was a broad discussion. It focused on contingencies that might suggest policy action by the ECB, and concentrated specifically on what the downside risk might be and what might make the downside risk, as we still see it, materialise. The reasons for the current situation in the emerging market economies are quite complex and certainly outside the control of euro area policy-making authorities or certainly outside that of monetary policy. Thus far, we have been watching these developments. Thus far, the euro area economy and euro area financial markets have shown a great deal of resilience with respect to these developments – in a sense, far more resilience than was the case almost a year ago, eight to nine months ago. This result is partly due to the fact that short-term volatility in interest rates has not been transmitted to long-term volatility of equal magnitude along the yield curve. In other words, one-year forward interest rates have remained anchored, irrespective of what short-term volatility looked like. And this is something that should be seen as one of the positive outcomes of our forward guidance. So basically, we are watching, monitoring this volatility. But the volatility is occurring within a range that we have set ourselves, and it has not been transmitted thus far, at least not to the long term. And we see this as the outcome of our forward guidance.

Question: I noticed you said that the January inflation numbers came in lower than expected. So, I am wondering, if next month’s inflation number comes in at the same level as for January, and is again lower than expected, would that be reason enough for the ECB to act and cut interest rates? And a second question on ending the sterilisation of bond purchases under the SMP: was that discussed and under what circumstances would you end sterilising?

Draghi: I will answer the second question first. It is one of the many instruments that we are looking at. It is not being discussed. We had a broad discussion about all the instruments. But let me say that the relevant committees of the ECB have been studying all these measures, so that by the time, and if, we decide to activate the measures, we are ready to go. What instruments we decide to activate will depend on the contingencies we have to face. And the two contingencies that I mentioned are really an unwanted tightening of the monetary policy that comes from the short-term markets and gets propagated to the long term and/or a worsening of the medium-term outlook for inflation.

On your first point, the question is what does a worsening of the medium-term outlook for inflation mean. Well, we have to ask ourselves what are the reasons for such an event. By the way, incidentally, we have acted in November already. We took action and now we are witnessing some of the responses of both financial markets and the real economy to that action. Of course, it is going to take a relatively long time for interest rates to propagate their action to the economy.

Let us ask ourselves what are the causes of such behaviour of inflation. First of all, we have to dispense once more with the question: is there deflation? And the answer is no. There is certainly going to be subdued inflation, low inflation for an extended, protracted period of time, but no deflation. The inflationary expectations continue to remain firmly anchored and we do not see much of a similarity with the situation in Japan in the 1990s and early 2000s. If we look at the definition of deflation, that is a broad-based fall in prices, self-feeding onto itself and happening in a variety of countries. We do not see that. Just to give you another piece of information: during the period of deflation in Japan, over 60% of all commodities experienced a decline in prices; the percentages for the euro area average are much lower.

We should also put these figures into perspective. First, if we look at low inflation rates in the euro area now, they are not much lower than those in the United States, with a recovery there, which is way more advanced than that in the euro area. Second, if we look back, we see that inflation following the previous two financial crises, the Asian crisis at the end of the 1990s and the 2009 Lehman Brothers crisis, was about the same. So, this gives some perspective.

I am not saying this to ignore the risk of having low inflation for a protracted period of time. It is quite clear that, first, adjustment with low inflation is more difficult, and second, the very fact of having low inflation for a protracted period of time is a risk in itself. So, it warrants close attention by the ECB. If we look, however, at the causes of this low inflation, we see that, primarily, it is driven by food and energy prices. The second cause might be weak demand and high unemployment.

Now, as we have seen over the last few months, there is a modest recovery that shows more encouraging signs. We see that the demand side is getting stronger, not weaker. As I have said many times, we have to be extremely cautious with this recovery, because it is still fragile, it is still uneven and it is really starting from low levels of activity. But, so far, it is proceeding.

We also ask ourselves whether there is any evidence of people postponing expenditure plans, which is something you would watch in a deflationary environment. And we do not have any evidence of this at this point in time. We see that consumer confidence is actually rising and that savings rates have been stable, at least until the third quarter of 2013, which is the latest data we have.

But, it is a complex picture because, on the other side of the scale, we see that the increases in value added tax rates have not been passed through in Italy or, so far, in France. And we have seen that the figures for retail sales over Christmas were not encouraging. So, this shows that, even though we have gradual signs of recovery, the pricing power of firms is still weak. Then, when we look at supply, we observe that much of the adjustment, much of the decline in core inflation, actually comes from the four programme countries: Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Greece. All in all, this would signal more of a relative price adjustment than of a deflation phenomenon.

So, I have tried to give you a sense of the complexity of the picture, which would explain why, before taking any decision today, we would wait.

Question: Back to inflation, even after your lengthy explanation. You mentioned taking more time, you mentioned in the introductory statement further information and analysis being available in early March. Is that an indication that maybe you’re postponing action, that you are postponing additional stimulus, rather than just deciding not to do it today? And what kinds of things should people who follow the ECB be looking at to see if your medium-term outlook on inflation is changing?

And my second question is on quantitative easing and some of the comments that you made in Davos. You mentioned the prohibition against monetary financing and that the ECB does not have bond purchase plans like the Fed, the Bank of Japan and Bank of England. Why is buying government bonds for monetary policy purposes monetary financing?

Draghi: The reason for today’s decision not to act s really to do with the complexity of the situation that I have just described, and the need to acquire more information. In this sense, today’s instance is different from what we had in November. Now, in what sense is it different? The macroeconomic projections by our staff, which will be coming out at the time of our monetary policy meeting in March, will contain, for the first time, forecasts for 2016, and that is a very significant change in our analysis, a significant change in the information set that we use for our analysis.

The second factor that led us to reflect is that when we look at monetary and credit developments by year end, which look subdued – although they are stabilising, especially the credit flows – we believe that, and we think we have evidence that, these figures are affected by banks’ behaviour in view of the asset quality review (AQR) performed by the ECB in the course of 2014, because the data upon which the AQR is going to be performed are data for year-end 2013. So, one would not rule out a certain behaviour by the banks that would like to present their best data by the end of 2013, which means that this is going to affect credit flows, which means that we may have different figures in the coming weeks about that.

The third reason is what we briefly touched upon before, which are the developments in the emerging market economies, and there the need is to look through this recent high volatility in these economies, in all parameters of these economies, and see whether this is a temporary phenomenon or something that is going to stay with us for some time. Clearly the consequences for world growth and world development are different. And also, the breadth of this weakness in emerging market economies is not clear yet. So we will need further analysis.

Finally, there is another piece of information which we don’t have yet and which is going to come out probably next week, and that’s the GDP figure for the last quarter of 2013.

But, having said that, as I have said several times we are willing to act and we stand ready to act. We confirmed our forward guidance, so interest rates will stay at the present or lower levels for an extended period of time.

About what I said in Davos: first of all, we see that lending is stabilising, but remains weak. Things may get better, but they may stay as they are, or even get worse. The question is, what are we going to do about that? First of all, we see that not all lending is actually doing poorly: if we look at corporate bond issuance – basically, lending coming from capital markets – that is not doing poorly. It’s the bank lending channel that we have to concentrate on. Incidentally, if you take the credit flows figures of the last two months – which are negative, but not as negative as before, in the sense that they are stabilising – and you add to this the corporate bond issuance by non-financial companies, by the corporates, you see that you are not exactly at zero, but you are very close to a level of zero change in credit flows. In other words, the corporate bond issuance almost compensates for the fall in credit flows in the last two months of the year. I am saying this because we have to focus on the bank lending channel.

Now, also, we have a piece of information which will be helpful in assessing the conditions of the banks at this point in time. We had a bank lending survey. A bank lending survey, amongst other things, assesses how credit standards change in time depending on different sorts of factors. One factor we look at is risk perception by the lenders, by the banks. And the fairly interesting thing is that when we look at the effect of a certain risk perception, we see that the effect of risk perception on bank lending in the euro area is by and large at the same level as it was in 2010, and even earlier, even at pre-crisis levels. So this doesn’t mean that risk perception has disappeared; risk perception is there, but its effect on tightening is considerably less than it was before.

All this shows not only that there is greater confidence in the banks, in the lending process – because we said that, really, confidence has increased since July 2012 – but also that this confidence is translating itself into a better lending condition. That’s another factor that we have to focus on.

We should also say a few words on the effect of the AQR on lending. It is pretty clear, also in view of what I have just said, that banks, in view of the AQR, had carried out some deleveraging, also in some cases significant deleveraging. And so the short-term consequences of the AQR are that banks have to clean up their balance sheets; they know that we will shed light on what is in their balance sheets, so they want to be presenting balance sheets that are clean, and this has a negative effect on credit. But, in the medium to long term, which is now, because the data are from 2013, the AQR will be positive for lending, because it will increase the confidence in the banking system, it will reopen capital markets for banks, as we are already seeing, and it will cause what supervisors call “prompt corrective action”, namely raising capital standards, provisioning and so on. And we are already seeing this by the way, and we are welcoming this action that takes place even ahead of our AQR. All this means that in the not too distant future we will have a more resilient banking sector capable of lending more than it would if the AQR had not been there. We tend to forget that basically concealing the evidence of the banks’ balance sheets, preserving their opaqueness, doesn’t help lending – it in fact hurts lending, so that is the other factor.

And finally, what I said, what I hinted at in Davos: asset-backed securities (ABS). We think that a revitalisation of a certain type of ABS, a so-called plain vanilla ABS, capable of packaging together loans, bank loans, capable of being rated, priced and traded, would be a very important instrument for revitalising credit flows and for our own monetary policy.

Incidentally, our own monetary policy is also going to benefit from the AQR because, if the bank lending channel works, we will see interest rates translating themselves into lower lending rates.

Question: Let me try and rephrase that question. Do you have any concerns at all about the legality of quantitative easing via government bonds in the euro area? And my second question is on the ABS. You have repeatedly spoken of this, and it was not the first time you mentioned this in Davos. I just wonder what time frame are you speaking about? How quickly can we create such a market? Is this something that could happen during the course of this year or would it take five years? And a question about your debate again: were any of the Governing Council members pushing for a rate cut this month?

Draghi: On the last question, there was a broad discussion where all instruments of monetary policy were talked about. But most, if not all, of the discussion was focused on examining the additional need for information and the uncertainty. That is the key substance of the discussion the Governing Council had.

On your first question, I have said repeatedly and I continue to say, that in our pursuit of our mandate of maintaining price stability, all the instruments that are allowed by the Treaty are eligible. There is no issue of legality. And at the same time the Treaty forbids monetary financing. So we know what is eligible and what is not eligible. I focused on ABS, on private sector assets, because we have to focus on the bank lending channel. But this does not mean that other assets are not eligible, provided this does not violate the monetary financing provisions: if I am not mistaken, it is Article 123 of the Treaty – it is not hard to remember. Again, the key thing is that it is in order to pursue our mandate of maintaining price stability, and I think we have to keep this in mind.

Question: Just a year ago, the Irish Government engaged in an arrangement whereby promissory notes that were used to recapitalise financial institutions were replaced by long-term bonds. At the time, the ECB took note of this but said it would have to review it to see if it was in compliance with monetary financing rules. Two questions. Number one: have you, or when will you discuss this? And number two: what kind of demands could you make from the Irish central bank if it’s found that this arrangement was indeed in breach of Article 123?

Draghi: Well, the second question I’ll answer immediately. We will see. We don’t know it in advance, we’ll have to see what we find out. And, concerning your first question, we are collecting all the necessary information and the assessment of the Governing Council will be known in due course, after the completion of this monitoring exercise.

Question: I have two questions. The first one is also on inflation. You have said that the inflation figures in January were also lower than expected for the ECB. I guess this will reinforce speculation that you have to revise downwards your 2014 projections in March. A lot of people say that this could be, or would be, a trigger for additional monetary easing. However, on the other hand, you have said that, we do not only have to look at the figures, but also at the reasons for low inflation. Does this mean that, even if you have to revise them downwards, this is not automatically a trigger for a further rate cut or something similar? And the second question is a more general one. Several times in the past you have stressed the need for clear communication, and you have introduced forward guidance to be more transparent. But, if one looks at the markets before today’s meeting, there was a high degree of uncertainty about how you would react to the latest developments and what you would decide. Does this mean that your communication strategy is failing or is it just the case that you cannot give more certainty if you yourself are uncertain? Thank you.

Draghi: If you define by uncertainty or poor communication the fact that we do not announce cuts by the date and the time two or three years in advance, yes, our communication is poor: we do not do that. Our duty is to give the markets not what you seem to be hinting at: it is to give them the clearest explanation of what our reaction function is. Well, of course, I am a biased observer, but I think that we have improved our communication on this. I think that the markets certainly understand our reaction function better than they did a year ago or even two years ago. There has really been some constant improvement here. We have introduced several changes to our communication and to the press conference.

Now I will turn to the first question. As you can see, I gave you a fairly complete and complex picture of what we look at in order to decide upon our reaction to an inflation rate which is going to stay lower for a protracted period of time. I think that what I have said before in these long answers is enough to construct a fairly accurate reaction function.

Question: I have two questions. First, to come back to the emerging markets, there is going to be a G20 meeting later this month: would you support coordinated action basically to try to help end the turmoil. And my second question is on interest rates and instruments. You say you are seeing a very long or a long period of low inflation. What instrument would be the best to counter that and why won’t you just cut rates if you are below target anyway?

Draghi: The response to the second question is that we want to see clearly beyond the current uncertainty. When I say that we foresee a low inflation rate for a protracted period of time, that is subject to the information we have now. That is why it is so important to analyse the information before taking decisions which will have an effect for a protracted period of time. As we know, changes in interest rates take time to affect the economy. I would say that since the markets stabilised, the time that it takes for changes in interest rates to affect the real economy has gone down. In other words, the effectiveness of our monetary policy has improved. But we want to see exactly what the forthcoming information will suggest in terms of causes, perspectives and the length of this phenomenon, and any price projection, any inflation projection we make is obviously subject to the information and conditional on the information we have up to that time, as is any action or decision we take.

On your first question, there have been calls for greater coordination in monetary policy following the spillovers that monetary policy decisions in one important monetary policy jurisdiction – not us – had on the rest of the world. Let me make a general point here. Each monetary policy authority, each central bank has its own specific mandate. The priority is always to comply with the mandate, which in our case is to maintain price stability. When you look closely at what the term coordination implies, strict coordination might imply that one authority, one central bank takes a decision which might not be what that authority would have taken if there were no coordination. And that is where such strict coordination becomes difficult. Because first and foremost we all have to comply with our mandate and mandates are decided by our legislators, national legislators. At the same time I think that exchanges of information and discussions are extremely useful. We have plenty of opportunities for such exchanges in the G20, as you said, in the BIS, in the IMF and in many other fora. If we think that this is not enough, we can certainly improve on it.

Question: The Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, Raghuram Rajan, has criticised the selfish economic policies pursued by advanced economies and has said that the international monetary cooperation has broken down. Do you share this idea? My second question is that you have said that there is a difference between the experience of deflation in Japan and the current situation in Europe. But we are living in a totally different world than in the 1990 and 2000s. Mr Rajan has said that inflationary pressure is common among the advanced economies. You may have a fresh view on that. What do you think about this situation? Thank you.

Draghi: Regarding the second question, the situation is completely different from what Japan experienced at that time in the sense that Japan had deflation and we do not. I already have gone through the long list of reasons why the situation is different, including the monetary policy activism of the ECB at a relatively early stage and the condition of the private sector balance sheets (of both banks and corporates) in the euro area relative to what it was at that time in Japan. But the other thing you said is absolutely right, there are certainly some global factors that keep inflation low. It is not only in the euro area. In the United States, inflation is higher than it is in the euro area, but still low – especially low if one considers the state of their recovery, which is way more advanced than ours.

The other question you asked was about coordination and the selfishness of the monetary policy authorities in the United States, Europe, the UK and Japan. Mr Rajan is really an excellent economist. What one would have to demonstrate to speak of selfishness is the following. One would have to show that monetary policy actions within the United States, the ECB and so on were decided for reasons other than for the sake of the mandate and that, as a result, they were harmful to other countries. As I said, the priority for all of us is compliance with our mandate, which for us is maintaining price stability and for the Federal Reserve Board is the dual mandate. But Mr Rajan is such a good economist and such an excellent central banker that he might have very interesting ideas about this issue and I am looking forward to discussing them with him at the next G20.

Question: Mr President, I have two questions. We have heard today long explanations about why the ECB is on standby mode, how more information is needed, how the picture is complicated and so on. Would you have the same cool attitude if the inflation rate were to be 3%, not below but above the medium-term target? Some observers talk about this and call into question the symmetry of the inflation target. What is your opinion on this? Second question: in the last few days, German politicians have strongly criticised the so-called “rotation votes” rule within the Governing Council. When Lithuania joins the euro, probably in 2015, the rule would be enforced and that means, for instance, that the Bundesbank will be excluded from voting in one of five sessions. Question: would you say that this rule, which was adopted ten years ago in a very different context, is still justified today at a time when all kinds of decisions are being made to preserve the euro area and by all members, if possible?

Draghi: No, I don’t have a cool attitude at all with respect to the present level of inflation rates. I just said that low inflation, these levels of inflation for a protracted period of time, are a risk on their own: are a risk for the recovery, are a risk for the weight of debt in real terms, and are a risk for a variety of reasons. So, let me say one more time that we are alert to this risk and we stand ready and are willing to act. That is a general point I want to make.

The second point is that, if you look at the ECB experience since its birth, it has delivered on price stability achieving an objective of being close to, but below, 2% in a very remarkable fashion. Some say more successfully than any other central bank, both while the ECB has been in existence and before. This also means that at some point inflation was way above 2%, and still the ECB didn’t act, yet at other times it acted, because what really matters is the medium-term outlook, and in assessing the medium-term outlook what matters are the causes that determine the rate of inflation. to be what it is. So, I would still claim that we have a symmetric attitude.

The second question is about rotation. First of all this is not a matter for central bankers, but for legislators. Second, it is in the Treaty. So it is a fact. I don’t know, people change the Treaty, people change rotation. But it is certainly not changeable easily and, in any case, it is not up to us. Having said that, I am absolutely confident that all national central banks will have plenty of opportunities to express their policy views and to decide accordingly and to contribute to the general policy decision-making, no matter what the rotation scheme is.

Question: First of all, you have spoken about the unevenness of the recovery. It would be great if you could also speak a little about the unevenness of the disinflationary dynamics. You mentioned that in the four programme countries, it owed something to adjustment, but we have also got quite significantly below target inflation in France and Italy. So, can you just comment a little bit on the disinflationary dynamics there? Secondly, on the point about the turmoil in emerging markets and central banks having to act with their own mandates. Okay, but weren’t a lot of those mandates created in an intellectual climate in which people thought inflation targeting plus a flexible exchange rate were enough for the stability of the global monetary system? Now, that that kind of intellectual orthodoxy has been found wanting, is it not a little bit of a cop-out to just say, “well, we have to act within our mandates” if those mandates are just going to lead to a lot of instability and a lot of playing in the global monetary system? And lastly, would it be possible for you to just clear up, once and for all, the issue about monetary financing – is it not the case that if you want to, you can just buy government bonds in the secondary markets? And that’s not prohibited under the Treaty?

Draghi: I will first answer your third question. Yes, it is possible. It has been done and it was not against the Treaty. Think of the Securities Markets Programme, that was such a case.

Then your first question was about unevenness, Unevenness of the recovery and, yes, unevenness of disinflation, too. I have said before that a good part of the subdued performance of core inflation is due to the subdued, very subdued, performance of core inflation in the programme countries. And some of it certainly is a part of a relative price adjustment that is welcome. And some of it is probably due to the weakness of demand and the high levels of unemployment which are still much higher in the programme, and in the stressed countries, than they are in other parts of the euro area. So, we are looking with great attention at these developments because there is no single clear-cut cause. There are two causes, and one of them would certainly have to be looked at with great, great attention.

On the second point: the mandates, coordination and cooperation. You know, first of all, that the present mandates were crafted at different times. But the issue of coordinating monetary policy in order to minimise spillovers from another country has been with us, I would say, since the World War II. It was with us in the period of fixed exchange rates, when coordination was at a maximum during the Bretton Woods period. And it has been with us after that, when we had flexible exchange rates. At times, these coordination efforts have been successful – if we think about the Louvre Agreement, the Plaza Agreement – in devising new systems of exchange rate regimes. So, one would certainly not rule this out. When this coordination does not hamper compliance with national mandates – neither at the time when it was decided, nor in perspective – then it’s certainly something that one can discuss. But one of the reasons why these coordination arrangements have failed is precisely that, at some point in time, they were going against compliance with national mandates. And all of us can well remember various examples of coordination arrangements that have collapsed because of this fact.

Question: My first question is, if you discussed today also the possibility of buying equities and the possibility of a rate cut? And my second question is, you said that the present level of inflation will be for many months. Don’t you think that this, in any case, so 0.7%, 0.8%, don’t you think that this is a sort of failure already of the central bank’s monetary policy?

Draghi: On the second point, as I said before, we discussed all instruments, but frankly we did not discuss buying equity. We have not reached that point yet.

On the first question, we are looking through this. The fact that we are spending so much time and effort in analysing inflation shows that we are still determined to achieve an inflation target of close to, but below, 2%. We have to judge in a global disinflationary environment, we have to judge our performance, according to whether in the medium term our target is being achieved.

Question: Two questions, first of all, again about quantitative easing, if the ECB ever were to embark on quantitative easing, would the fact that there is already in place an outright market purchases programme – the OMT – be an impediment to buying government bonds or other assets in the markets? I am just talking about a theoretical hypothesis here. And my second question is about the AQR. The press release about the AQR mentions the fact that, together with Common Equity Tier1 (CET1) instruments, additional capital instruments that mandatorily convert into CET1 may be eligible. I was wondering if among those instruments the ECB could also consider hybrid securities and if those hybrid securities could be part of hypothetical market purchases by the ECB?

Draghi: Mr Constâncio who actually delivered the communication together with the Chairwoman of the Supervisory Board, Danièle Nouy, last Monday, will respond to the second question.

On the first question, I may be wrong but I do not see, off hand, any relationship between the two programmes. OMT is a well-specified programme that could be activated if certain conditions are verified and it addresses risks to price stability that could originate from redenomination risks. No, I would not say, off hand, that there is any relationship there.

Constâncio: First, just a reminder that this possibility, which is indeed in the information note that we published, is subject to several conditions. First, it can only be used in the adverse scenario of the stress tests. Why? Because we said for the adverse scenario, the capital requirements may not be demanded immediately. It is different if it results from the AQR or from the baseline scenario – then of course any shortfalls would have to be satisfied with other instruments. For the adverse scenario, which is a scenario that has some degree of risk of happening but it is not a certainty that it will happen, these other types of hybrid are accepted. That is the first condition. The second condition is that they have to be totally mandatory. It is something that must be in the contract, or, if you wish, in the terms of insurance, of those instruments – namely that the supervisor can convert them into capital. It has to be there. And the third condition is that any trigger for the conversion has to be such that it is related to the threshold of the adverse scenario. These three conditions have to be fulfilled. As you see, it is a relatively narrow thing.

Regarding the possibility of the ECB purchasing such instruments, it was never discussed and I think it will never be discussed, let alone decided.

Comentarii

Adauga un comentariu

Adauga un comentariu folosind contul de Facebook

Alte stiri din categoria: Noutati BCE

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%, in cadrul unei conferinte de presa sustinute de Christine Lagarde, președinta BCE, si Luis de Guindos, vicepreședintele BCE. Iata textul publicat de BCE: DECLARAȚIE DE POLITICĂ MONETARĂ detalii

BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) a majorat dobanda de referinta pentru tarile din zona euro cu 0,75 puncte, la 2% pe an, din cauza cresterii substantiale a inflatiei, ajunsa la aproape 10% in septembrie, cu mult peste tinta BCE, de doar 2%. In aceste conditii, BCE a anuntat ca va continua sa majoreze dobanda de politica monetara. De asemenea, BCE a luat masuri pentru a reduce nivelul imprumuturilor acordate bancilor in perioada pandemiei coronavirusului, prin majorarea dobanzii aferente acestor facilitati, denumite operațiuni țintite de refinanțare pe termen mai lung (OTRTL). Comunicatul BCE Consiliul guvernatorilor a decis astăzi să majoreze cu 75 puncte de bază cele trei rate ale dobânzilor detalii

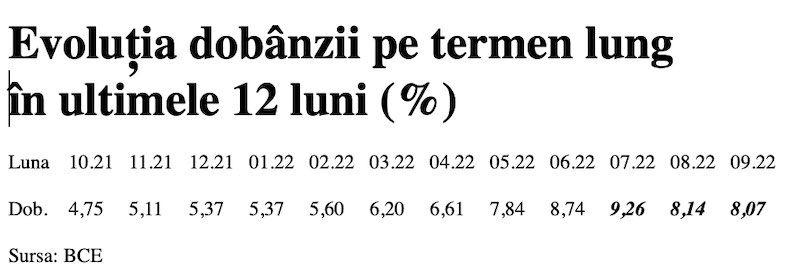

Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Dobânda pe termen lung pentru România a scăzut în septembrie 2022 la valoarea medie de 8,07%, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator, cu referința la un termen de 10 ani (10Y), a continuat astfel tendința detalii

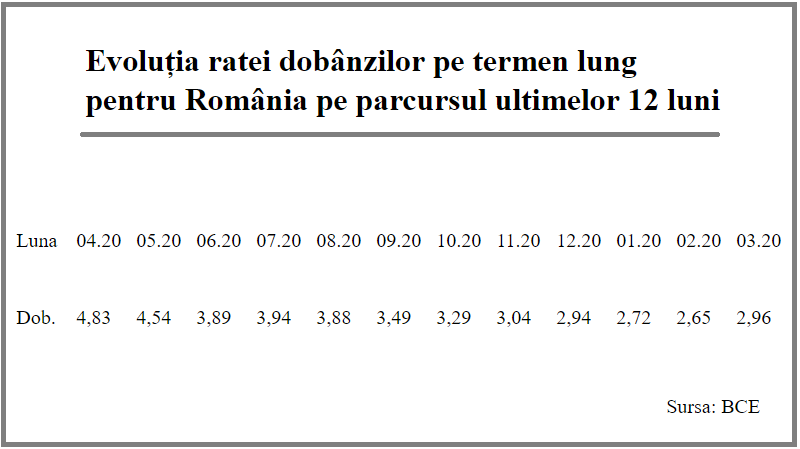

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Rata dobânzii pe termen lung pentru România a crescut la 2,96% în luna martie 2021, de la 2,65% în luna precedentă, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator critic pentru plățile la datoria externă scăzuse anterior timp de șapte luni detalii

- BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

- Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

- Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

- BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

- BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

- BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

- ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

- ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

- Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

- Deciziile de politica monetara ale BCE

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent după primele două luni, mai mare cu 25%

- Deficitul contului curent, -0,39% din PIB după prima lună a anului

- Deficitul contului curent, redus cu 17%

- Inflatia a încheiat anul 2023 la 6,61%, semnificativ sub prognoza oficială

- Deficitul contului curent, redus cu o cincime după primele zece luni ale anului

Legislatie

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

- Reguli privind stabilirea ratelor de referinţă ROBID şi ROBOR

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

- Parlamentul dezbate marti legile de plafonare a dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor cesionate de banci firmelor de recuperare (actualizat)

Anunturi banci

- Bancile comunica automat cu ANAF situatia popririlor

- BRD bate recordul la credite de consum, in ciuda dobanzilor mari, si obtine un profit ridicat

- CEC Bank a preluat Fondul de Garantare a Creditului Rural

- BCR aproba credite online prin aplicatia George, dar contractele se semneaza la banca

- Aplicatia Eximbank, indisponibila temporar

Analize economice

- România - prima în UE la inflație, prin efect de bază

- Deficitul comercial lunar a revenit peste cota de 2 miliarde euro

- România, 78% din media UE la PIB/locuitor în 2023

- România - prima în UE la inflație, prin efect de bază

- Inflația anuală, în scădere la 7,23%

Ministerul Finantelor

- Datoria publică, imediat sub pragul de 50% din PIB la începutul anului 2024

- Deficitul bugetar, deja -1,67% din PIB după primele două luni

- Datoria publică, sub pragul de 50% din PIB la finele anului 2023

- Deficitul bugetar, din ce în ce mai mare la început de an

- Deficitul bugetar după 8 luni, încă mai mare față de rezultatul din anul trecut

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

- Taxa de reziliere a abonamentului Vodafone inainte de termen este ilegala (decizia definitiva a judecatorilor)

Stiri economice

- Inflația anuală a revenit la nivelul de la finele anului anterior

- Pensia reală de asigurări sociale de stat a crescut anul trecut cu 2,9%

- Producția de cereale boabe pe 2023, cu o zecime mai mare față de anul precedent

- România, țara UE cu cea mai mare creștere a costului salarial

- Deficitul comercial în prima lună a anului, la cea mai mică valoare din septembrie 2021 încoace

Statistici

- Care este valoarea salariului minim brut si net pe economie in 2024?

- Cat va fi salariul brut si net in Romania in 2024, 2025, 2026 si 2027, conform prognozei oficiale

- România, pe ultimul loc în UE la evoluția productivității muncii în agricultură

- INS: Veniturile romanilor au crescut anul trecut cu 10%. Banii de mancare, redistribuiti cu precadere spre locuinta, transport si haine

- Inflatia anuala - 13,76% in aprilie 2022 si va ramane cu doua cifre pana la mijlocul anului viitor

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

- Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

- O firma care a facut un schimb valutar gresit s-a inteles cu banca, prin intermediul CSALB

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, în expansiune la început de an

- România, pe locul 2 în UE la creșterea comerțului cu amănuntul în ianuarie 2024

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, în creștere cu 1,9% pe anul 2023

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, în creștere pe final de an

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, stabilizat la +2% față de anul anterior

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate

Ultimele Comentarii

-

nevoia de banci

De ce credeti ca acum nu mai avem nevoie de banci si firme de asigurari? Pentru ca acum avem ... detalii

-

Mda

ACUM nu e nevoie de asa ceva .. acum vreo 20 de ani era nevoie ... ACUM de fapt nu mai e asa multa ... detalii

-

oprire pe salariu garanti bank

mi sa virat 2500de lei din care a fost oprit 850 de lei urmand sa mi se deblocheze restul sumei ... detalii

-

Amânare rate

Buna ziua, Am rămas în urma cu ratele , va rog frumos sa ma ajutați cumva , soțul a pierdut ... detalii

-

Am depus bani și nu mi au intrat in cont

Sa se rezolve ... detalii